Lord Leighton's Hidden Arcadia

Leighton’s sexuality has never been positively identified; a brilliant technician and academic painter, there are many images of voluptuous women within his body of work. However, it is the homoerotic nature of many of his works that I wish to focus on. Ostensibly, the subject of The Hit is that of father teaching his young son how to hunt with a bow and arrow, but the subtext is homoerotic and presents the Uranian ideal in a variety of references.

Conveniently, the action takes place in warmer climes than Victorian London and this facilitates the half-nakedness of the beautiful young man and the almost total nakedness of the beautiful boy. The immaturity of the boy allows Leighton to depict him almost completely naked; paradoxically, as with similar dress codes in earlier paintings of the crucifixion, the invisibility of the child’s genitals serves to highlight them, particularly as a long, dangling strand of material stands in place of his penis. The leopard skin that the man wears around his waist indicates his sexual maturity so, immediately, the unequal status of the two figures is powerfully conveyed. The father’s hands enclose the boy’s, controlling the action and the firing of the arrow; the boy, therefore, becomes a cipher for the father’s actions. The painting has an underlying theme of initiation into the rites of manhood and it contains a strong subliminal idea of sexual penetration (i.e. the fired arrow which, so the title of the painting tells us, has successfully found its target) and the passing down of this sexual act from older to younger. The success of the image is that the idea is conveyed equally, whether taken as heterosexual or a homosexual motif; the man could as well be initiating the boy into either; he has shown the boy how to successfully shoot his arrow. There is an erotic intimacy in the man’s face pressed into the boy’s neck, and the placement of the boy’s naked buttocks between the man’s open thighs reinforces this.

If we refer to two preparatory drawings made by Leighton prior to painting The Hit! we can see an even greater homoerotic potential presented itself. In the first (fig. 2), we see two rough sketches of the man and boy. In both pairings, the boy appears more curvaceous and femininely ‘coquettish’; indeed, in the right hand sketch, the exaggerated, slightly distorted buttocks of the boy better indicate that he is firmly sitting on the older man’s lap – a detail not used in the final painting.

In the squared-up sketch (fig. 3), which Leighton eventually used for The Hit!, the boy has an almost rapturous expression on his face, at the firing of his arrow. As we can see, Leighton toned this down considerably in the painted version.

Fig. 3. Frederick Leighton, Study for The Hit, 1893.

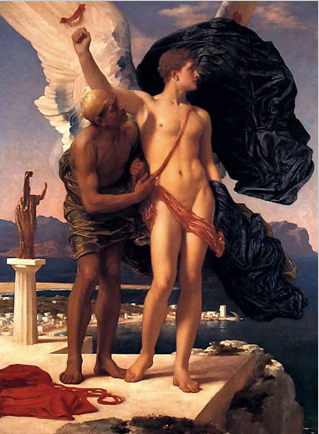

In Leighton’s earlier painting, the Greek mythological Daedalus and Icarus (c1869) (fig. 4), we again see the Uranian ideal of an older male instructing a younger. We come to this image at the moment that Daedalus is warning his son Icarus of the dangers of flying too high; a warning that the young man will ignore, to his peril. If we bypass the familial relationship, the subtext is also homoerotic. The elder (unbeautiful) man, who’s life experience is evident by his sunburnt ‘outdoors’ skin, appeals to the beautiful depilated youth, who Leighton has rendered epicene by idealisation. The youth possesses a beauty of classical perfection, made almost fully visible by a fortuitous gust of wind that has whipped away his prophetically shroud-like wrap. This same wind will soon carry him up towards the sun, which will melt his wings which, so the story tells us, are constructed of beeswax-and-feathers. But Leighton has been unconcerned with the logistics of such manufactured aerodynamics and aside from fixing a useful handhold on each wing, he has given them a perfect, seamless appearance. This elevates Icarus to the status of angel; indeed, Leighton seems to be saying that a youth so preternaturally beautiful must surely be an angel. Apparently, and impossibly, Daedalus is tying the wings onto Icarus’ back by a single strand of vermillion gauze, which also usefully obscures (and thereby draws attention to) the youth’s genitals – which are surely as minute and infantile as any cherub’s. As in Hit!, the end of this flowing material serves as a phantom penis; this half-erection, complete with a stylised, rounded end, juts from the crotch of the beautiful youth; the slight curve of the material around his thigh intensifies this effect. Diagonally at counterpoint to this, the youth’s raised right arm serves as a subliminal erection, rising tellingly above the head of the supplicant older man,

Fig. 4. Frederick Leighton, Daedalus and Icarus, 1869.

who appears to be whispering ineffectually into the hairless armpit of his inamorato. When the painting was unveiled, more than a few Uranian hearts must have fluttered at the poignant hopelessness of the pictorial relationship, in which Leighton’s beautiful doomed youth sans merci, holds all the cards.

Uranian love gloried in the thrill of the chase. Once captured, once ‘had’, to use Oscar’s phrase, the glorious chase, the moment of capture, of sexual surrender, could never be replicated. The Uranian lover’s erotic doom was an endless cycle, an unrelenting grailquest of desire and satiation which could never end in lasting peace and fulfilment. (Neil McKenna, The Secret Life of Oscar Wilde, Century, London, p. 89)

How comforting it must have been for these same men, cognisant of the secret codes and messages contained in these and other works of art, to feel a validation of their sexuality in a time where their sexuality had no name; they were not alone, there were others like themselves within this secret club. As long as the secret remained such, they and their ilk could walk the Elysian Fields, at least in their imaginations.

Comments

Post a Comment