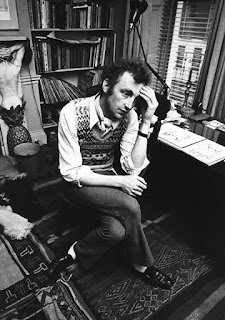

Afternoon Tea with Patrick Procktor (1983)

In the summer of 1983, I was in London, from Melbourne, on a 12-month Travelling Fellowship, which eventually turned into 18-months. In the months before I left Australia, I had written to a number of well-known British artists, whose work I admired, stating that I would be in London shortly, and that I’d welcome the possibility of a meeting. I received a few replies. One was a postcard from Derek Boshier, which featured one of his then recent paintings - an image of a naked cowboy floating against a lurid black and orange sky. It read, “Hi Steve, Unfortunately, I now live in Texas, so will be unable to meet you for now. But I may be in London in a few months. Perhaps we can meet then. All Best Wishes, Derek.” He had interspersed his text with small line drawings of heads in profile. Another of the postcards I received was from Patrick Procktor. It featured an C18th painting from the National Gallery. It read, “Hello Steve, Yes, do